My phone vibrated against my ribs. A low, angry buzz.

In my world, unknown numbers mean one of two things.

Blood or steel.

It wasn’t a bust. It was the school.

The secretary’s voice was clipped. My daughter, Lily. A problem.

She used a phrase that didn’t compute.

Academic dishonesty.

Lily alphabetizes our canned goods for fun. She doesn’t know how to cheat.

I told them I was on my way.

There was no time to scrub off the three-day stakeout.

No time to change out of the ripped jeans or the hoodie that smelled like stale coffee and desperation. The fake tattoo on my neck was peeling.

Good.

Let them see the monster they already imagined.

My rusted-out undercover sedan groaned into a parking spot between two gleaming SUVs. Parents stared. They saw the grease, the dirt under my nails, the exhaustion etched into my face.

They saw a threat.

The school office went silent when I walked in. The air turned thick and heavy.

The woman at the desk peered at me over her glasses. Her expression said I was something she’d found on the bottom of her shoe.

She pointed. Room 302.

The hallway was a sterile white tunnel. My work boots made ugly, thudding sounds on the polished floor.

I could feel the cold weight of my badge against the small of my back. It was the only clean thing I was wearing.

The classroom door was ajar. I stopped. I listened.

And that’s when I heard it.

My daughter’s voice. Small. Broken.

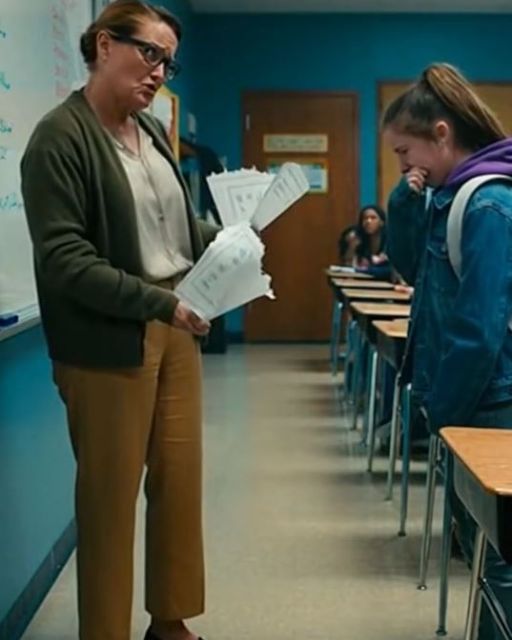

Then another voice. Sharp. Dripping with smug satisfaction.

“Perfect scores are not for people like you, Lily,” the teacher said. “I’ve seen your father drop you off. I know what you come from.”

My vision tunneled. The blood in my veins turned to slush.

“He helps me study,” Lily whispered.

The teacher let out a short, ugly laugh. “That man? He looks like he can barely spell his own name. You cheated. Admit it and we can move on.”

“I didn’t,” Lily sobbed.

I peeked through the crack in the door.

I saw the test paper in the teacher’s hand. The big, red 100 at the top. I saw Lily’s hands, clenched into tiny, white-knuckled fists.

“I have a policy against grading trash,” the teacher said.

Rip.

The sound was louder than a gunshot.

She tore the perfect score straight down the middle. Lily flinched.

Rip.

She tore it again. Into quarters.

“You get a zero,” the teacher said, letting the pieces drift to the floor like dead leaves. “Now go to the principal. I’m supposed to call your father, but I doubt a man like that bothers to answer his phone.”

She stopped talking.

Because a shadow now covered her desk.

I was in the doorway.

I didn’t say a word. I just let her look. Let her see the man she’d already put in a box.

Her face cycled through confusion, then annoyance, then a blotchy, panicked red. She drew herself up.

“Sir,” she snapped, her voice trembling just a little. “This is a private conference. I’m going to have to call security.”

I took a slow step into the room.

The children were silent stones in their seats.

I walked past them, my eyes locked on hers, until I was kneeling beside my daughter.

Her face was a mess of tears.

“Daddy, I didn’t,” she choked out. “I promise.”

I wiped a tear from her cheek with my thumb. “I know, sweetheart. I know.”

I stood up.

The teacher was backed against the whiteboard now. A cornered animal.

“You think I’m stupid?” I asked. My voice was quiet, a low gravelly thing I usually saved for interrogation rooms.

“I’m calling the police,” she stammered, fumbling for her phone.

“No need,” I said. “They’re here.”

I reached for my back pocket.

She flinched. A kid in the front row ducked under his desk.

Slowly, I pulled out my wallet.

I flipped it open.

The gold detective’s shield caught the cheap fluorescent light and threw it right back in her eyes.

Her jaw went slack. Her eyes darted from the badge to my face, from my face to the badge. The two images wouldn’t connect in her brain. She was glitching.

“Pick it up,” I said.

She stared blankly.

“The test,” I said, my voice flat. Hard. “Pick. It. Up.”

She didn’t move.

“Now.”

And the woman who had just torn my daughter’s world apart crumpled to her knees.

She started gathering the scraps.

Her name was Mrs. Albright. I made sure to read the plastic nameplate on her desk as she scrambled for the pieces of my daughter’s heart.

Her hands shook. She couldn’t look at me. She couldn’t look at Lily.

She could only stare at the floor, at the evidence of her own cruelty.

I put a hand on Lily’s shoulder.

“Let’s go see the principal, honey,” I said, my voice soft again. For her.

I kept my eyes on Mrs. Albright. “Bring the test.”

The walk to the principal’s office was a new kind of silent. It wasn’t the hush of a stakeout. It was the heavy quiet of a child trying to hold herself together.

Mrs. Albright followed us, her heels clicking a frantic rhythm on the tiles.

The principal, a man named Henderson with a soft face and a tie that was too tight, stood up when we entered. He saw a well-dressed teacher, a crying child, and a man who looked like he’d just lost a bar fight.

His face settled into a mask of weary officialdom. He was already on her side.

“Mr. Henderson,” Mrs. Albright began, her voice recovering its sharp edge. “This man barged into my classroom. He was aggressive. He terrified my students.”

She was trying to build her own narrative. Frame me as the villain.

I’d seen it a thousand times in the box. The guilty always talk first.

I stayed quiet. I let her spin her story.

She claimed she had “strong reasons” to suspect Lily of cheating. That there had been a “dramatic and inexplicable” jump in her performance.

She held out the four ragged pieces of paper. “I was following school protocol for suspected academic dishonesty.”

Henderson nodded gravely, looking at me. “Sir, while I understand you’re upset, we do have procedures here.”

I looked at him. I mean, I really looked at him. I let him see the patience draining out of me.

“Is it procedure to call a ten-year-old’s father a bum?” I asked.

Henderson blinked. “I’m sure that’s a misunderstanding.”

“Is it procedure,” I continued, my voice level, “to tell a child she comes from trash?”

Mrs. Albright paled. “I never said that!”

“The entire class heard you,” I said. “Thirty witnesses. You want me to start taking statements from ten-year-olds? Because I will.”

I turned to Henderson. “I want my daughter’s academic file. Now.”

He hesitated, looking to Mrs. Albright for support. She just stared at her shoes.

He sighed and tapped a few keys on his computer. A printer in the corner hummed to life.

He handed me a thin stack of papers.

I fanned through them. Perfect attendance. Glowing comments from previous teachers. Straight A’s.

“A dramatic jump in performance, you said?” I asked Mrs. Albright, holding up the report card from last semester. “Looks like she’s been a perfect student since kindergarten. The only thing that changed this year was her teacher.”

I placed the papers on Henderson’s desk.

“My daughter doesn’t cheat. She studies. I study with her every night. After my shift.”

I let that hang in the air.

“I work long hours, Mr. Henderson. But I’m never too tired to help my daughter with her times tables or her state capitals. Maybe if Mrs. Albright had bothered to ask instead of judging, she’d know that.”

Mrs. Albright found her voice again, a shrill, desperate thing.

“He’s trying to intimidate me! He flashed a badge! He’s using his position to threaten me!”

Henderson straightened his tie. “Is that true? Are you here in an official capacity?”

“No,” I said honestly. “I’m here as a father.”

I leaned forward, placing my hands on his desk. “But I can come back in an official capacity. I can investigate a case of child endangerment and targeted harassment by a public employee. We can make this a much bigger problem for your school, Mr. Henderson. Your call.”

The man’s professional facade finally cracked. He was a bureaucrat, not a fighter. He wanted this to go away.

“Look,” he said, trying for a compromise. “Clearly, there have been some regrettable words exchanged. Mrs. Albright, you were out of line. Sir, your methods were… unorthodox. Why don’t we agree to let Lily retake the test tomorrow? We’ll wipe the slate clean.”

I almost laughed. “Wipe the slate clean?”

I looked at Lily, who was watching me, her eyes wide.

“She didn’t do anything wrong. She aced the test. She earned a perfect score. You’re not wiping away her achievement because your teacher is a prejudiced bully.”

I took the four pieces of the test from Mrs. Albright’s trembling hand.

“I want this test taped back together. I want it graded, and I want that 100 put into the grade book. And then I want a written apology from Mrs. Albright to my daughter. In front of the entire class she humiliated her in.”

Henderson looked horrified. “We can’t do that. It would undermine her authority.”

“Her authority is already gone,” I said. “She destroyed it herself.”

Something was wrong. Henderson’s defense of her was too strong. It wasn’t just about procedure. It was personal.

My cop brain started working, looking for the angle.

My eyes drifted over Henderson’s desk. It was neat. Organized. A picture of his family. A stack of files.

On top of the stack was a transfer request. For a student named Daniel Albright.

I looked at Mrs. Albright. Then back at the file. The pieces clicked into place.

“Daniel Albright,” I said out loud. “Your son?”

Mrs. Albright froze. Henderson’s face went from pale to ghostly white.

“He’s applying to Northwood Preparatory Academy, isn’t he?” I said. It was a long shot, a guess based on the neighborhood.

The look on her face told me I’d hit a bullseye.

Northwood was one of the most exclusive, and expensive, private schools in the state. Getting in was next to impossible.

“That has nothing to do with this,” she snapped.

“Doesn’t it?” I mused. “That’s a tough school to get into. Even tougher to afford on a teacher’s salary.”

The whole ugly picture started to form in my mind. This wasn’t just about a single test.

I looked back at Henderson. “Let me guess. You wrote his letter of recommendation.”

He didn’t answer. He just adjusted his tie again, a nervous tic.

They were in it together.

I stood up. I knew I wouldn’t get justice here. Not today. Not in this office.

“We’re done here,” I said. I took Lily’s hand.

“This isn’t over,” I told them. “Not by a long shot.”

Back at the precinct, I couldn’t let it go. It gnawed at me.

The look on their faces. The fear. It was more than just getting caught being a bully.

It was the fear of being exposed.

I couldn’t use department resources for a personal vendetta. But I was a detective. My brain was a resource.

I started with public records. Property deeds, tax filings.

Mrs. Albright and her husband, a mid-level accountant, lived in a house far bigger than their salaries should allow. They had two new cars.

And Daniel’s tuition at Northwood was fifty thousand dollars a year.

It didn’t add up.

I started thinking about her classroom. The way she talked about “people like you.”

It wasn’t just classism. It was a business model.

I spent my next day off at a coffee shop near the school. I just watched.

I saw the parents dropping off their kids. I saw the shiny SUVs and the luxury sedans.

And I saw Mrs. Albright talking to a few of the mothers. A quiet exchange. A slip of an envelope into her hand.

I knew what it was. I’d seen deals like it go down on street corners.

She wasn’t just a teacher. She was running a scam.

I went home and talked to Lily. It was hard. I had to ask her about her friends.

“Honey,” I started, sitting on her bed. “Does Mrs. Albright ever offer special help to some of the kids?”

Lily nodded. “She does tutoring. For math.”

“Who goes to the tutoring?”

She named three kids. All of them from the wealthiest families in the school.

“And how are they in math?” I asked.

Lily shrugged. “They used to be bad. Like, really bad. But now they always get A’s. Even when they get the answers wrong on the homework.”

My blood ran cold.

She wasn’t just tutoring them. She was fixing their grades.

But why tear up Lily’s test? Why make such a public scene?

And then I understood.

It wasn’t enough for her clients to get A’s. The other smart kids, the ones who earned their grades, had to be brought down.

Kids like my Lily. Kids from the wrong side of the tracks, whose perfect scores made her paying customers look less exceptional.

She wasn’t just lifting her clients up; she was pushing everyone else down to create the curve.

My daughter wasn’t an inconvenience. She was a threat to the business.

Now it was a police matter. It was fraud. It was extortion.

I took my findings to my captain. He was an old-school cop who believed in right and wrong.

He listened to the whole story. He looked at the financial records I’d pulled.

He looked at the picture of Lily on my desk.

“Go get her,” he said. “Do it by the book. But go get her.”

We set up a sting. It was beautiful in its simplicity.

We had a female officer, Detective Miller, pose as a wealthy mother new to the district. She was decked out in designer clothes and drove a loaner car from the department’s impound lot.

She scheduled a meeting with Mrs. Albright to discuss her “struggling” son.

I was in a surveillance van parked across the street, listening to every word.

Miller played her part perfectly. She was worried, anxious.

“I just want what’s best for my son,” she said, her voice laced with manufactured panic. “I’ll do anything to make sure he gets into a good school.”

Mrs. Albright’s voice was smooth as poison. “I understand completely. There are… standard tutoring packages. And then there are more comprehensive ‘premium’ packages.”

“Premium?” Miller asked.

“It guarantees success,” Mrs. Albright said. “I ensure that your son is seen in the best possible light. I take care of any… inconvenient competition.”

My hands clenched into fists. She was admitting it.

“How much for the premium package?” Miller asked.

“Ten thousand dollars,” Mrs. Albright said. “Cash. For the semester.”

That was it. That was the nail.

We let Miller hand over the marked bills. We let Mrs. Albright put the envelope in her purse.

We gave her ten minutes. We let her walk back to her classroom, feeling like she’d won.

Then we moved in.

I didn’t go in first. I let the uniformed officers handle it. It was better that way. More official.

But I was right behind them.

I watched them walk into Room 302. I watched the look of smug satisfaction on Mrs. Albright’s face curdle into pure, abject terror.

She saw me standing in the doorway. She knew.

They cuffed her right there, in front of the whiteboard.

Principal Henderson came running, protesting, babbling about the school’s reputation.

My captain just looked at him. “Your reputation is the least of your worries right now. You’re an accessory to felony fraud.”

Henderson’s jaw snapped shut.

The aftermath was messy. It was all over the local news.

The school board fired them both. Other parents came forward. A dozen families had been paying her. Another dozen had kids who had been targeted and bullied just like Lily.

It was a bigger, uglier mess than I could have imagined.

But for us, for Lily, it was finally over.

A few weeks later, there was a special assembly at the school.

The new principal, a kind woman who seemed genuinely committed to fixing the damage, called Lily up to the stage.

She held up a piece of paper.

It was Lily’s test. The four pieces were carefully taped together, encased in a plastic sleeve. The big red 100 was clear as day.

The principal apologized to her on behalf of the entire school district.

She said Lily represented the best of their students: honest, hardworking, and resilient.

The entire auditorium stood up and applauded. Her classmates, her friends. They cheered for her.

I stood in the back, out of sight. I’d worn a suit for the occasion.

And I felt a single, hot tear roll down my cheek.

That night, I was tucking her into bed.

The framed test was on her nightstand.

She looked at me, her eyes clear and bright again.

“You’re a hero, Daddy,” she whispered.

“No, I’m not, sweetheart,” I said, my voice thick. “I’m just your dad.”

She shook her head. “You saved me.”

I thought about that for a long time after she fell asleep.

I didn’t feel like a hero. I just felt like a father who had done what any father would do.

But maybe that’s the whole point.

We live in a world that’s quick to judge. People look at a torn hoodie and greasy hands and they see a bum. They see a threat.

They don’t see the long hours, the missed dinners, the quiet sacrifices. They don’t see the heart underneath.

Justice isn’t always about kicking down doors and making arrests. Sometimes, it’s about standing up for a little girl who did her best.

It’s about refusing to let the world tell you or your children who they are.

It’s about making sure that a perfect score, earned with honesty and hard work, is never, ever treated like trash.