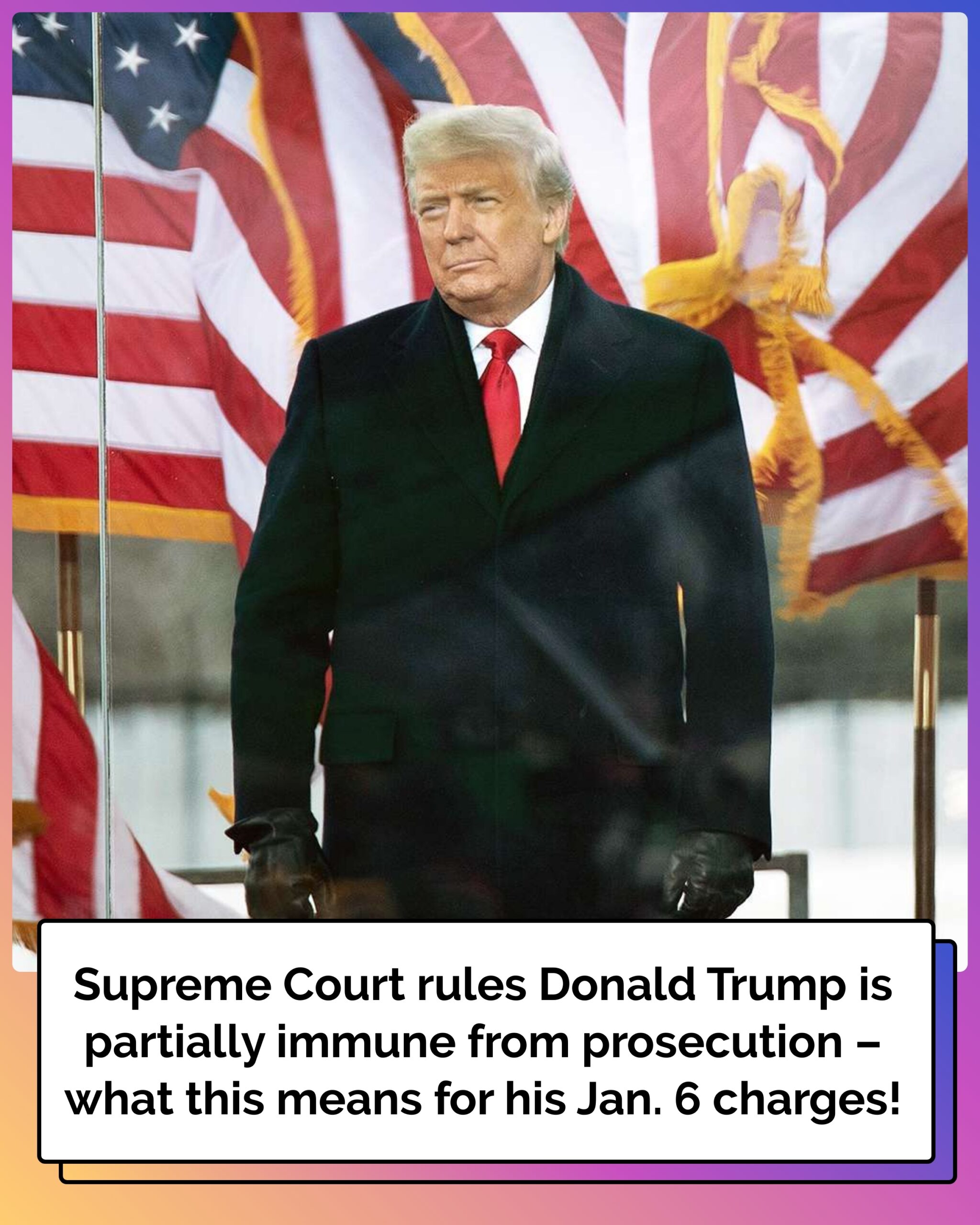

The hotly anticipated ruling centers around whether Trump can stand trial for potentially criminal actions he took as president

Donald Trump has been deemed partially immune from his 2020 election subversion charges in one of the Supreme Court’s highest-profile cases of the term.

On Monday, July 1, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 against Trump’s claim that he enjoys immunity from prosecution as a whole — but they still handed him a win, saying that he is absolutely immune from being charged for “official” presidential acts.

In a complicated opinion that revisits the extent to which former presidents can be held accountable for their White House actions, the majority asserted that there should be a clearer distinction between official presidential acts and private acts that happen to be done by a president.

“The President enjoys no immunity for his unofficial acts, and not everything the President does is official. The President is not above the law,” the court’s syllabus reads. “But under our system of separated powers, the President may not be prosecuted for exercising his core constitutional powers, and he is entitled to at least presumptive immunity from prosecution for his official acts.”

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP/Getty

Some of Trump’s Jan. 6 charges, the Supreme Court said, stem from actions he took in his official capacity as president and are therefore shielded from prosecution. But his actions that fall more in line with those of a political candidate or private citizen — not a sitting president — are fair game.

The decision kicks the case back down to a lower court, which must now figure out whether any of the allegations in the Jan. 6 case fall under the category of “unofficial” acts, and whether a fair Jan. 6 trial could move forward with the Supreme Court’s ideology in mind.

Can Trump Still Go on Trial Before the November Election?

The clock is ticking before the November election, and Trump’s legal team hoped that at the very least, the Supreme Court case would delay proceedings long enough for him to evade prosecution before voters take to the polls.

The Justice Department has an unwritten “60-day rule,” in which federal prosecutors are discouraged from taking major steps in a criminal case within 60 days of an election if the case could have political implications. It’s a standard practice, but not a firm guideline, and in 2016 it was seemingly disregarded when FBI Director James Comey publicly reopened an investigation into Hillary Clinton’s email servers days before the presidential election.

U.S. District Judge Tanya Chutkan, who is presiding over Trump’s federal Jan. 6 case, is not bound by that guidance as a member of the judiciary — and since the criminal case was brought by the DOJ well in advance of the election, she could still choose to schedule a trial close to the election and federal prosecutors would be required to participate.

The primary issue for Chutkan is determining what Trump can still be prosecuted for, if anything, given the Supreme Court’s broad interpretation of what counts as an official act.

And then there’s the logistical nightmare of reworking a case and getting it to trial with less than five months until Election Day. Special counsel Jack Smith has made clear he is ready to work on a rushed timeline, but he can only do so much with the slow-moving nature of the justice system — and Trump’s knack for finding ways to delay.

The Supreme Court will be watching how Chutkan sorts out his charges, and could potentially intervene again if the justices disagree with her decision-making.

According to a Politico/Ipsos poll conducted in March, three in five Americans want to see the former president stand trial on his Jan. 6 charges before casting their vote in November.

WIN MCNAMEE/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

The former president was indicted in four separate criminal cases in 2023.

The first indictment, in his New York “hush money case,” led to a jury conviction in May on 34 felony counts of falsifying business records to conceal a scheme to corrupt the 2016 presidential election.

In Trump’s federal classified documents case — which centers around how he handled top secret documents at Mar-a-Lago after leaving the White House — he faces 40 felony counts, including a violation of the Espionage Act. The trial has been repeatedly delayed by Trump-appointed District Judge Aileen Cannon, and was indefinitely postponed in May due to “various pending pre-trial motions.”

The third indictment came from his federal Jan. 6 case. Following the “most wide-ranging” investigation in DOJ history, according to the attorney general, he was charged with conspiracy to defraud the United States, conspiracy to obstruct an official proceeding, obstruction of and attempt to obstruct an official proceeding, and conspiracy against rights.

Trump’s final criminal case similarly deals with how Trump and his allies conspired to overturn Georgia’s 2020 presidential election results. Trump faces 10 felony counts, including a violation of the Georgia RICO Act. After a series of challenges and delays, an appeals court confirmed in June that the trial will not begin before Election Day.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor Pens Fearful Dissenting Opinion in the Immunity Case

Zooming back from the Jan. 6 indictment itself, liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor expressed fear for democracy with the court’s new precedent that a president enjoys absolute immunity from broadly defined “official acts.”

“When [the president] uses his official powers in any way, under the majority’s reasoning, he now will be insulated from criminal prosecution,” Sotomayor wrote in a dissenting opinion. “Orders the Navy’s Seal Team 6 to assassinate a political rival? Immune. Organizes a military coup to hold onto power? Immune. Takes a bribe in exchange for a pardon? Immune. Immune, immune, immune.”

Justice Sonia Sotomayor

The relationship between the President and the people he serves has shifted irrevocably. In every use of official power, the President is now a king above the law.

She added that, in effect, conservative justices are sending the following message with their landmark decision: “Let the President violate the law, let him exploit the trappings of his office for personal gain, let him use his official power for evil ends. Because if he knew that he may one day face liability for breaking the law, he might not be as bold and fearless as we would like him to be.”

Sotomayor admonished the “cloak” of immunity that’s now been placed upon all past and future presidents, and concluded by saying, “With fear for our democracy, I dissent.”

Justices Elena Kagan and Ketanji Brown Jackson joined Sotomayor’s dissenting opinion.