I was only at the auction because my friend Dean owed me money. One of those grimy storage lock-ups on Route 8, full of mildewed textbooks and broken microwaves.

But one box had a label in marker: Walt, Summer ‘79.

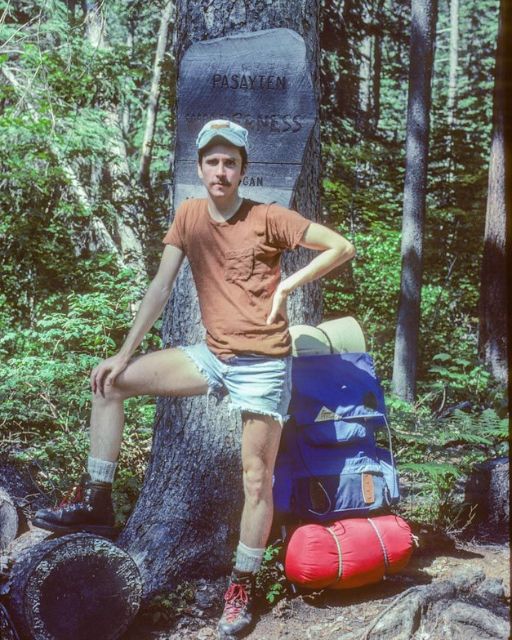

Inside: camping gear, a hand-cranked flashlight, and this photo.

My uncle Walt, posing like some Appalachian explorer—short shorts, boots, a smug hand on his hip. Behind him, a tree carved with PASAYTEN WILDERNESS.

Washington state.

He told us he’d never been west of Indiana. Said the “furthest he’d ever wandered” was the Toledo outlet mall.

But that’s definitely him. The same crooked front tooth, same thick wristwatch. And I know that hat. I have it in a drawer at home.

I showed the photo to my mom. She stared for a solid minute and said, “That’s not Walt’s backpack.”

And she was right. The tag stitched onto it read B.H.

It only took me a second to remember—Bram Hollinger. A name my grandma used to hiss when she thought no one was listening.

Then I flipped the photo over. One sentence in faded pen: “Don’t tell your mom. She’d never forgive me.”

That was the moment my stomach flipped. Walt always seemed like the steady one. The boring, corn-fed uncle who grilled burgers on the Fourth of July and kept crossword books in his glove compartment.

But this? This was something else. Something hidden.

That night, I couldn’t sleep. I sat in bed with the photo under my lamp, studying every detail—the wild ferns at their feet, the cigarette dangling from Bram’s fingers, Walt’s nervous half-smile. Something about it didn’t read as pure fun. It looked like a secret frozen in time.

By morning, I was already on a plan. I knew Bram’s last name—Hollinger. I remembered that my grandmother once mentioned he’d been a teacher. I spent two hours digging through old high school yearbooks online until I found him. Mr. Hollinger. Chemistry. Retired in 1996.

He had lived two towns over.

I drove out there with Dean, who thought the whole thing was hilarious.

“So your uncle was in the wilderness with some guy your grandma hated? What, you think he murdered him or something?”

“No,” I said. “I just think he lied.”

Dean smirked. “Same difference, man.”

We found Bram’s old house, now rented out to a young couple. The woman, Kendra, was folding laundry on the porch and looked surprised when I asked about him.

“Mr. Hollinger? He passed away in 2005. Cancer, I think. Sweet guy. A little private, but he used to send us postcards from state parks.”

She let us look around the garage, where some of his things had been boxed up and never claimed. Among the stacks, I found a folder of Polaroids bound with a rubber band.

There were maybe thirty photos, and in at least ten of them, my uncle Walt was standing right next to Bram—at Yellowstone, the Grand Tetons, even in front of a Vegas casino.

My heart kicked. He had been everywhere. They had been everywhere.

One photo caught me off guard. Bram had his arm slung over Walt’s shoulder, and Walt was laughing. Like really laughing. The kind of belly-laugh I never once saw at Thanksgiving.

On the back, in Bram’s loopy handwriting: “Walt, you make the West feel like home.”

I stared at that line for a long time.

It didn’t take a genius to figure out what was going on. My uncle hadn’t just been traveling with a buddy. He’d been in love. Maybe secretly. Maybe for years.

I didn’t tell Dean. Not right away. I wasn’t sure it was my story to tell.

Instead, I asked my mom again. We were eating Chinese food on her patio, and I waited until her wine glass was nearly empty before I asked, “Do you remember Bram Hollinger?”

She flinched. “That man? Of course. He tried to ruin Walt.”

“What do you mean?”

“He was obsessed with him. Always showing up. Sending letters. My mom told Walt to cut him off after college. Said he was ‘confused.’ And Walt—he always did what he was told.”

I wanted to scream. My mom sounded like she was reading from a 1950s playbook. Instead, I just said, “Did he ever tell you he traveled with Bram?”

“No. Because he didn’t.” She paused. “Walt never left Ohio.”

I didn’t push. I knew the photo in my pocket said otherwise.

A week later, I went to visit Walt at his apartment. He was sitting in his recliner watching a baseball game with the sound off. He looked older than usual. Smaller.

I pulled the photo out and handed it to him without a word.

He didn’t even blink. Just stared at it for a long time, then said, “That was the first time we ever saw snow in July.”

“You lied to us,” I said, but there was no anger in it. Just sadness.

He nodded slowly. “I had to.”

He told me the whole thing, piece by piece. How he met Bram in college. How they’d snuck away one summer, just the two of them, in a beat-up van with a cooler full of peanut butter sandwiches and maps they barely read.

They hiked, they slept under the stars, they kissed when they thought no one was around. It was a perfect, impossible summer.

But when they came home, Walt’s father found a letter Bram had written him. A love letter.

He never told me what the letter said. Only that after his dad read it, everything changed.

He was told to cut Bram off. To “fix himself.” And out of fear, he did.

He stayed in Ohio. Got a factory job. Lived a quiet life. Bram wrote him, maybe a dozen times. Walt never answered.

“Do you regret it?” I asked.

He looked out the window. “Every damn day.”

I wanted to cry. Not just for him, but for the decades he lost trying to be someone else.

Then he said something that hit me like a gut punch: “You know, the weird part is—your grandma never threw that hat away. She hated Bram, but she never tossed the hat.”

That’s when I got an idea.

Two days later, I went back to the couple who had rented Bram’s house. Kendra still had a few boxes left. She let me go through them alone this time.

In one folder, I found a stack of letters. Every single one had been sent back unopened, marked in shaky handwriting: RETURN TO SENDER.

But the last one—dated 2004—was different. It had been opened.

Inside was a note, short and written in blue pen: “Still waiting. Pasayten, if you ever want to finish the trail.”

That was the same place from the first photo. The same name carved into the tree.

I knew what I had to do.

I printed the photo. Booked the flight. And three weeks later, I was standing next to Walt on the edge of the Pasayten Wilderness.

He hadn’t hiked in years. His knees weren’t what they used to be. But he looked alive. Like he’d been plugged back into the world.

We walked for half a day before we found the tree. The bark had grown thick over the carving, but it was still visible. Faded but there.

There was no sign of Bram, of course. He’d passed away years ago. But I think Walt hoped for a trace. A footprint. A memory.

He pulled out a small tin from his pack. Inside was a folded piece of paper—a note he never sent.

He read it aloud. It was just three sentences.

“I’m sorry. I loved you. I should have said it sooner.”

He buried it under a rock beside the tree. Then he looked at me and said, “That’s the first honest thing I’ve done in a long time.”

On the flight back, he told me he felt lighter. Like some weight he’d been dragging for decades was finally gone.

He didn’t start marching in pride parades or telling the whole family. He didn’t need to. He just started talking a little more. Laughing a little more.

At Thanksgiving, he brought out old photos. Of mountains. Of waterfalls. Even one of him and Bram playing cards at a picnic table.

My mom didn’t say much. Just quietly put another scoop of mashed potatoes on his plate.

And that was enough.

Sometimes we don’t need permission to tell the truth. We just need time. And a little courage.

Walt passed away two years later. Peacefully. With a photo of Pasayten framed on his bedside table.

We buried him with the hat. The one Bram gave him.

And at the funeral, my mom leaned over and whispered, “He was brave, in the end.”

Yeah. He was.

So if you’re holding back something real—something that matters—don’t wait until the world gives you permission. Sometimes the bravest thing you can do is be honest with yourself.

Even if it takes decades.

If this story meant something to you, share it. Someone else out there might be holding onto a truth they’ve buried for too long. And they might just need to know they’re not alone.